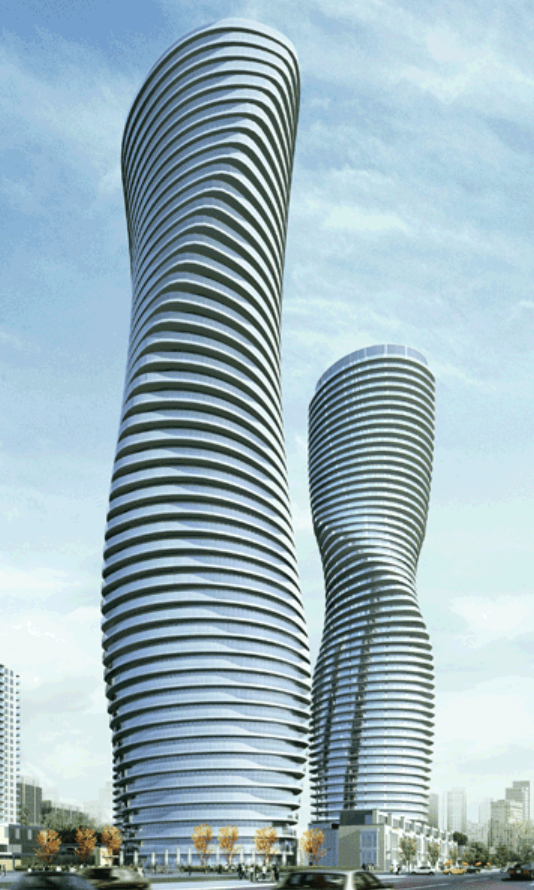

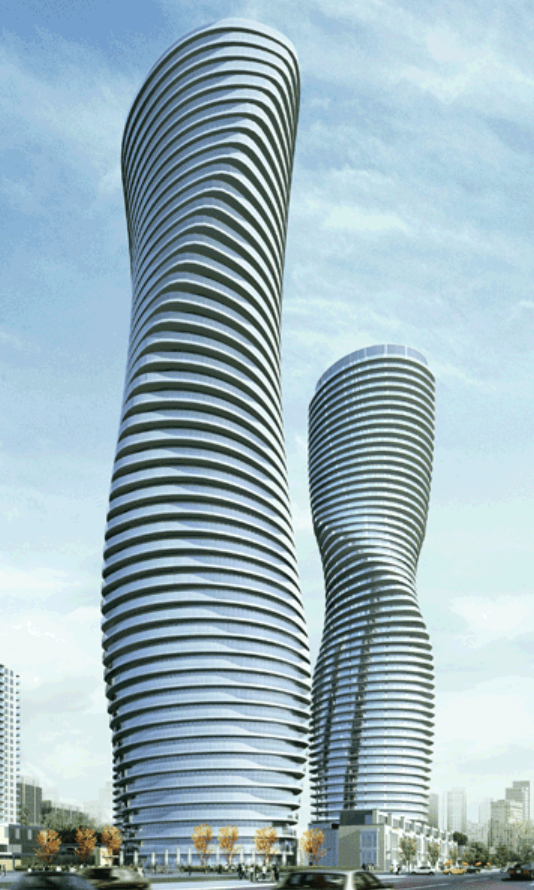

It’s a pileup of floor plates that cavort and shimmy in and out of an elliptical tower shape. A shebuilding, with curves of glass dressed in a corset of horizontal ribs. If Issey Miyake were an architect instead of a fashion designer, he might have imagined the Absolute Tower just this way: an intelligent, shifting sheath that sashays around the body.

Architecture lives in Mississauga. At long last. In a city with a reputation for building an unstoppable dull-scape, the Absolute condominium development has created some serious architecture envy. Last week, there were fireworks exploding from the 56-storey marvel by Beijing-based MAD Architects, to celebrate the tower’s topping-off. Yes, I know. To people living in major urban centres across Canada, where architecture is increasingly understood as a civic badge of honour, the making of an icon in a fiefdom of sprawl is unthinkable – an oxymoron.

Commonly referred to as the Marilyn, the tower rotates clockwise between one and eight degrees. Supporting walls run longer or shorter depending on the configuration of the floor plates. C-shaped walls around the elevator shafts are used as key structural elements and to house mechanical systems. In the tower’s midsection, 10 floors rotate at the full eight degrees, creating the striking sashay in the building profile.

The horizontal ribs are, in fact, cantilevered balconies, which run seamlessly around the curves of the condo tower, one on top of the other all the way up. We’ve become conditioned to the architectural daring of art galleries and museums. The Absolute is a condo tower – a triumph of organic movement – brought to life by private developers.

Next to the Marilyn is another she-building, not as visually arresting, but a worthy partner to the compelling courtesan. Under serious cloud cover, when the crystal-grey glass on the buildings grows dark, they appear to be a pair of elongated armadillos. The towers are the spectacular standouts in a five tower complex called Absolute. The first three, with conventional designs, are already occupied. Marilyn will be open next year; her shapely sidekick, the year after that.

MAD Architects are significant as designers that have freed (like a handful of others) the condo tower from its slab rigidity. They know how to capture the naturalistic, irregular stacking that can occur, say, in China’s mountain ranges, while maintaining the vertical height of a skyscraper.

Architecture that pushes and pulls along floor plates (rather than the jagged volumes of a Daniel Libeskind or Zaha Hadid) has been gaining currency of late. In Chicago, there’s the Aqua Tower with its dynamic wave-like balconies, by Studio Gang. There’s the Gwanggyo Power Centre in Seoul, its mixeduse buildings shaped like cones, each floor lined with box hedges, by Rotterdam-based MVRDV architects.

Recently, MAD has taken the Absolute concept much further by proposing a heavily greened skyscraper for Chongqing, China. But, remember, all you design aficionados in Toronto or wherever you may be, the slipping, stacked phenomenon started first in Mississauga.

Whose afraid of a Philistine mayor when you have passionate builders and city staff? Serious kudos goes to Absolute’s partnership builders, the local Cityzen Development Group and Fern brook Homes. Fern brook president, Danny Salvatore, tells me that he’d grown tired of nearly 20 years of building subdivisions: “I knew that in order to put me ahead of the competition, I had to do iconic buildings.” At the same time, the Mississauga planning department, led by Edward Sajecki, made it clear that the city, which does not impose height limits, was looking for a gateway building for its downtown.

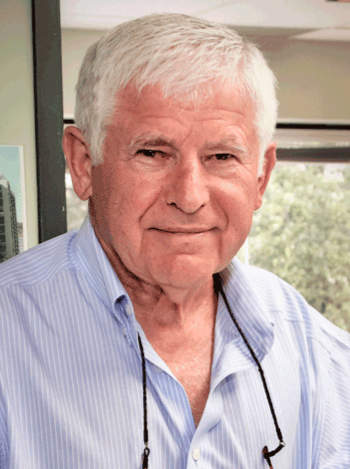

In 2005, the builders launched an open, international design competition that attracted 92 submissions. Ma Yansong, who studied at Yale, led MAD to victory with a tower of svelte gentility. The jury endorsed the design, but fretted about its buildability. So did Salvatore. To deal with that issue, he hired Burka Varacalli Architects as local design architects, and his own long-time colleague, structural engineer Sigmund Soudack, to weigh in with his 45 years of engineering experience.

Last week, when I visited the Absolute at Hurontario Street and Burnhamthorpe Road, howling winds and construction dust were blowing in fierce gusts around the concrete tower. Deep within the building, Soudack, known as Siggy, and who still speaks with an accent from his native Poland, unrolled architecture drawings in the on-site building office. With him was his colleague, Yury Gelman, an engineer, originally from Ukraine, who has experience designing gravity-based structures that sit on the bottom of the ocean within the Hibernia oil fields.

Anthony Pignetti and Sergio Vacilotto from nearby Dominus Construction Group were also there to discuss the challenges of building the tower. Their enthusiasm was palpable, and together they formed a team with cultural and professional ties from around the world.

Consensus quickly formed around the practical, lyrical properties of concrete. “Concrete is plastic,” says Soudack. “You can shape it. We love concrete.” Building a rotating skyscraper on shale required intense collaboration between architects, engineers and builders. With every step, the team had to embrace the irregularity of the building plan: that every suite on every floor was uniquely configured.

About a month after the MAD design was released to the public, the Marilyn was sold out to people who didn’t mind paying an extra 20 per cent to address the expensive building problem – a vote of confidence for architectural significance over formulaic housing.

As boulevards go, six-lane Hurontario wins a prize for uninviting and depersonalized. No café culture here. A meanness to the median and to the narrow sidewalk that runs past slab apartment towers. But streetscape improvements in the form of native grasses, benches and planters are promised for next year. And although funding hasn’t been nailed down, transit authority Metrolinx appears committed to the idea of a light-rail transit system to be planted along Hurontario and around a loop in Mississauga’s downtown.

Driving away from Mississauga, I glance in the rear-view mirror and see the Absolute’s silhouette. There she is: jutting her hip onto the horizon, pushing away from the mediocrity that lines the boulevard in an unlikely but lucky corner of the world, where banality has been trumped by a tribute to the female form.

Original Source:

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/home-and-garden/architecture/like-marilyn-herself-the-absolute-tower-is-smart-sexy-built-to-impress/article623098/